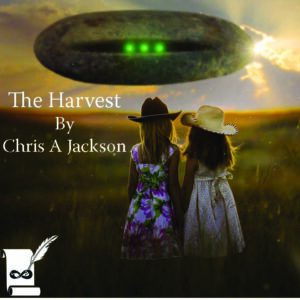

This is a story I wrote as part of the Hersher Project International Writers Group, one of our monthly exercises (though I’ve forgotten what the precise exercise was!). Image by Stefan Keller from Pixabay Enjoy.

The Harvest

Chapter One: To Worlds Unknown

by Chris A. Jackson

“Harvest time’s comin’, Josef.”

“Yeah, it’s comin’.” He picked up his gloves and headed for the door, aware of the fear in Mira’s voice. “Comes every year. Not much to be done ’bout it.”

“Meanin’ you don’t want to do nothin’ ’bout it!” She rose from the table and turned her back on him, her youngest balanced on her hip. Thera would be four months old in just a few days, and Mira would be pregnant again right after harvest, just like every other woman on Earth.

“Mira, you know I can’t do nothin’ ’bout it.” Josef put down the gloves and clasped his big, strong, farmer’s hands together until his knuckles cracked. “They come and harvest ever’ year; have been since before my dad’s dad was born and will long after we both go. Can’t fight ’em. Not with nothin’ but hoes and picks.”

“Can’t or won’t?” She turned to face him, tears streaking her face, her knuckles white on the knots of her apron strings.

A shrill cry sounded from the back of their house, their second youngest, Donny, who would be two this year. The young ones didn’t like when their parents fought.

Josef cringed at the noise and lowered his voice. “Attackin’ hover sleds with farm tools, while they got shockers and net-casters ain’t my idea of a fight, Mira. We’d all be taken, and what then? What about the kids? Two more get our place and work our land.”

“And who will they take, Josef? Who goes and never comes back?” She clutched Thera to her breast and clenched her jaw against the tears. “Fourteen babies I birthed in this house, Josef. Four been harvested, and the two eldest girls already been scarred and set up with strangers as husbands who won’t ever father their own babies. One birth a year, same time ever’ year, with no idea who the father really was, nor how them babies was conceived. I tell you Josef, it ain’t right! It ain’t much better’n not livin’ at all!”

Donny squalled anew, and their third youngest, Moira, joined in.

“So what’ll you have me do, Mira?” His quiet tone screamed more desperation than any raging tirade ever could. “You tired of livin’? You want us all to be harvested? The four youngest is too young to fight. What happens to them?”

“I don’t know, Josef? I want to live, but this ain’t much better than goin’ wherever the harvest takes you.”

“You don’t know that, Mira. You don’t know what happens to them what go.”

“No, I don’t, but I know that we’ll all go eventually, Josef. We, you an’ me, will be harvested. Taken onto one of their flyin’ cities and be gone forever. Or we’ll die here, fightin’ not to be taken. You tell me which is worse.”

Josef stared at his hands, strong, talented only with the tools of a farmer, and utterly incapable of saving his children from being taken away by those who controlled every facet of human life. They made it rain. They made it snow. They made the women of every household pregnant exactly once every year. They made the soil fertile and made the animals docile. They even made the sun and the moon, some said, but Josef didn’t believe that, though he did believe they made the stars, or at least some of them. The regular pattern of lights in the night sky seemed a made thing, like the bricks of a wall or stitches in a mended sock.

And they took people away, every year, one from every other home, and sometimes a whole family would go, and a young couple, strangers to one another, would be given their land. And the young woman would be pregnant without ever having known a man’s love. And the cycle would repeat, every year.

“What can we do?” Josef looked up from his hands, now clenched into impotent fists of rage, to Mira, the woman he had come to love over the years. Time and caring for children together had made them a family. “How can we fight them?”

“I don’t know, Josef.” She sat down and bounced the fussy baby on her knee, smiling through her tears at the child’s flailing hands and cherubic features. Josef was dark skinned, with very curly short hair, while the child was very fair with red hair. Mira was fair skinned with dark hair. Neither knew how the pregnancies happened, only that when a woman was taken and given land with a man, she had a small pink scar on her abdomen, and would be pregnant in the early fall every year from then on until she died or was taken by the harvest.

“Maybe you should talk to Lorence. Joni says he found something in that cave up on the ridge, a white powder that burns.”

“He digs in bat shit and finds salt that burns, yeah, I heard it from Tobi.” He gave a snort of laughter. “I suppose it can’t hurt. If digging in shit will save us from Them, I’ll be the first in line with a shovel. Can’t be worse than spreadin’ manure on the fields.” He hefted his adze and thrust the door open with his toe. “I’ll talk to Lorence tonight, after sundown. I’ll be on the south twenty weedin’ if you need me.”

“You be careful, Josef,” she said, standing and moving to where he stood in the doorway.

“Careful?” A harsh snort of laughter escaped his broad nose. “Ain’t nothin’ but weedin’ woman. I ain’t gonna cut of my toe or nothin’.”

“You know what I’m talkin’ ’bout,” she said, grasping his arm and pulling him to her. Their lips met, eyes open, as was their custom. It always brought a smile, their eyes close, reflecting one another’s souls, which was worth all the pain in the world.

***

“So, what’s this stuff you found, Lorence?” Josef rubbed his hands together under the water of the horse trough. He brought a double handful up to his face and scrubbed the day’s sweat off, sputtering and snorting to get the dust out of his nose.

“That’s disgusting,” Lorence said, not a hint of apology in his tone.

“What?” Josef toweled his face dry with the hem of his shirt.

“Never mind.” Lorence turned away and walked toward his small cabin. He and Joni had lived in this place for only four years, but it had been Lorence’s father’s place, so it had been the only home he’d ever known. “Come on in the house and I’ll show you.”

“Awright.” Josef followed the much shorter man into the cabin, ducking under the doorway. He didn’t have to duck in his own house, but this wasn’t his house. Lorence didn’t even come to his shoulder, and seemed to Josef so thin and frail that he might blow away in a strong breeze, but Lorence managed his fields well enough, supplying more than enough to feed his family and donate to the common. Josef didn’t know how the little man managed it, but he couldn’t argue that he did.

“Joni, we got a guest!” Lorence announced, stirring his wife from the daybed where she was suckling their youngest. They had only two living children. Their first had been born cold, and their second had already been taken by the harvest, though barely two years old. Joni hadn’t spoken much since that little boy had been harvested. “You want a drink, Josef?”

“Sure.” Joseph had secretly hoped Lorence would make the offer. One of the reasons Lorence was such a popular fellow with his neighbors was the quality of the corn whiskey he distilled in his basement. He traded most of it for seed and scrap metal, broken plows, harrows and tools that They replaced every year with the harvest. Nobody knew what Lorence did with the metal, but they were eager to exchange a broken spade for a flask of high-grade hooch.

“Right kindly of you.” Josef nodded to Joni as she handed him an earthenware cup and filled it half full of clear liquid from a large jug.

She didn’t reply, just returned the cork to the jug and put it back on the sideboard, never even stopping the baby’s noisy suckling. She just sat back down, eyes vacant, fearful, lost. The coming harvest weighed heavily on her. It weighed heavily on them all.

“Come on down the cellar, then,” Lorence said, moving to the large trap door in the cabin’s floor. He lifted the hatch and trundled down the steep steps into the dark. Josef followed more carefully, grateful as an oil lamp flamed up below, illuminating the maze of contraptions cluttering the cellar.

“Sure beats me what the hell all this stuff is, Lorence.” Josef sipped his cup and stifled the urge to cough as it burned his throat. “Where do you get all this?”

“Made most of it.” The smaller man shrugged and wound his way along the narrow track through the morass of junk and half-built contraptions. “I don’t even know what some of it does, yet. I will someday, though. Sometimes I just start buildin’ and when it’s done, it does what it does.”

“That’s downright nuts, Lorence.” Josef downed the rest of his whiskey and set the cup aside on a cluttered table. “How do you know what you’re buildin’ if you don’t know what it’s supposed to do?”

“Don’t know, Josef. Sometimes the feelin’ just comes over me and I start in, like you with your plow and team. You cut the straightest row in the region. Can you tell me how you do it?”

“Nope,” Josef admitted with a chuckle.

“Now, I can’t cut a straight row to save…” The small man fell silent for a moment, his eyes drifting up to the cabin overhead. “Anyway, you come on and let me show you what I found.”

“Sure.” Josef stepped over to where the smaller man stood in front of a wide table.

“Now, let me tell you, I ain’t told many about this, and I don’t want rumors about it spreadin’ round. You see what it is, you may get ideas about what you might get if you tell Them about it. If you do, I swear on all I have and all I know, I’ll use it against you. Now, that might not make sense to you now, but it will in a bit. Now lift the other side of this table with me.”

“What?”

“This table,” Lorence said, bracing himself and lifting on the heavy metal slab. “Lift this side with me.”

“Awright.”

Josef set his considerable strength to the task, and to his astonishment, as the two lifted, the entire table and a good portion of the floor tilted up on cunningly hidden hinges. None of the junk on the table rolled or clattered to the floor, and Josef realized it was all welded to the tabletop. The whole thing was a fake, a disguise to hide…

“Well, would you look at that!” Josef peered into the dark passage beneath the table. Steps led down.

“Follow me down.” Lorence picked up the lantern and started down the stone steps. “Stay right behind me. The way turns some, but there’s no branches. If the light goes out, just stand still ’til I get it lit again.”

“Huh? What do you mean if the light goes out?”

“It gets drafty sometimes. Usually not, but it does. Now stay close.”

The two men descended the stair, barely two steps apart. They continued down until Josef had lost count of the steps and his legs began to burn. They passed narrow fissures in the rock though which he felt air flowing. When they finally came to the bottom, what he guessed was probably two hundred feet below the cabin’s floor, Lorence worked the latch on a heavy metal door and ushered him into a long, narrow room.

“What the hell?” Josef’s breath caught in his throat, though whether from the acrid smell of the room or the bizarre contraptions cluttering the tables near the door, he didn’t know. “What’s all this stuff? Who dug this place?”

“My Pa dug this out,” Lorence said, moving to light two more lanterns. They were set near the door, far away from the two long tables that dominated one end of the room. “Took his whole life to do it. He built stuff, too. He made the forge upstairs. He started out just fixin’ plows and such for folk, but then he started tinkerin’ with stuff. I used to watch him when I was a boy, and I learned a lot from what he did.” Lorence fell silent again for a moment, then shook himself and said, “When They took him, he told me to carry on. His last words. I just picked up where he left off.”

“And this?” Josef said, pointing to a cast iron pot over a low flame. It smelled horrible. “What’s this?”

“This is what I found, Josef. This is what we can use against Them, but I need someone to help me figure out how. I’m a builder, not a planner.”

Josef swallowed, staring down at the bowls of white, yellow and black powder, the flickering flames, the bubbling pots of foul-smelling liquid, and thought he was truly going crazy when he said, “Okay, Lorence. Show me what this stuff does, and I’ll try to help.”

***

“So, after I dry this stuff, then scrape it together, mix it with the charcoal, some sugar, and roll it all into a paste with beeswax, I pack it into one of these cast iron balls.”

“Why cast iron?” Josef’s head ached with the aftereffects of the whiskey and the long diatribe of his neighbor. He didn’t know if Lorence was crazy, or if he was crazy for listening.

“’Cause cast iron breaks up nice.”

“Breaks up?” Josef couldn’t believe what he was hearing. “How do you break cast iron?”

“Watch.”

Lorence picked up one of the little “caps” he’d shown Josef earlier and pushed it into the small hole in one of the packed cast iron spheres. The cap had a short bit of waxed tallow that Lorence had said would burn even when it was wet, like oil on water. He held one end of the tallow to the flame of one of the lamps until the waxed string began to sputter and burn.

“Cover your ears!” Lorence heaved the small sphere down the length of the long room.

As the sphere rolled, Josef took the other man’s advice and pressed his palms to his ears. He was glad he had when the tiny little ball of metal erupted in a blinding flash and a deafening CRUMP. The entire end of the room was obscured in dust and rubble that rained down from the solid rock walls and ceiling. A few shards of broken metal rattled down the hall toward them, some clattering and clanking among the equipment. The end of the hall was a good fifty paces away.

Joseph reached down and picked up one sharp spall of broken cast iron. It was hot, almost too hot to hold, but he tossed it from palm to calloused palm long enough to let it cool, then looked at it. The shard was as long as the last joint of his index finger, and was sharp on all edges. He imagined what would have happened had he been standing close to such an explosion.

When his ears stopped ringing, and some of the dust settled, he turned to the shorter man and asked. “How many of these can you make before harvest?”

***

Josef stood with his neighbors as the hover sled descended. Four of Them stood at its prow in front of the long empty bed, soon to be filled with men, women and children, the harvested.

Never again, Josef thought, clenching his hand in his pocket, secretly wishing that he would be the first to be taken. Mira stood to his other side, and their children behind them. All was in order for the harvest.

The hover sled settled and two of Them waddled off the edge onto the short grass of the field, the thick, shiny scales of their faces and arms glistening in the sun. Three short legs gave them a strange, rolling gait, and each held a long shock rod between two of their three short, three-fingered hands. The other two stayed aboard the craft, half hidden behind a wide control console. One, Josef knew, was the ‘chooser’, the one who would send the pain to the harvested.

“Take me,” Josef muttered under his breath, clenching his jaw so tightly that his teeth hurt. “Take me first.”

“Let The Harvest begin!” one of Them slurred from one of its three wide, lipless mouths. The eye above that mouth blinked, and a thick, yellow tongue flicked out. It rapped its shock rod on the ground. The tip flared with blue light, and the crowd of huddled humans shuddered. “Those who feel the call will step forward!”

It made a gesture to one of its troop on the sled, and the chooser manipulated something on the panel before it. Josef held his breath, willing the call to come to him, but a gasp to his right told him that it would not be.

He turned, and sorrow gripped his heart as Lorence’s wife Joni turned, handed her infant child to her husband and walked toward the sled. Lorence stumbled, and Josef reached out to steady him just as the smaller man surged forward.

Josef’s huge hand closed on Lorence’s arm like a vice, hauling him back into line, clutching him close before the two of Them with the shock rods noticed.

“Don’t, Lorence!” he hissed in the man’s ear, exerting enough pressure with his grip to threaten breaking the smaller man’s arm. “You fuck this up, and Joni dies for nothin’!”

“But… I…” His tear-streaked face looked up at Josef with such anguish that the larger man almost let go, almost let him die to save his already doomed wife.

“I know, Lorence!” Josef said, pulling the man close. The baby in his arms started to fuss and cry. “And she knows, my friend. She knows.”

Josef felt his friend turn to look at his wife as she stepped obediently up onto the sled. He turned, just in time to see the smile on her face, and the smoke twisting up from the pocket of her dress.

Then Joseph smelled the acrid smoke of a burning fuse.

“Let go of my arm, Josef,” Lorence said in a deadly calm tone.

Josef looked into the man’s utterly mad eyes, and let go.

Joni pulled her hand from her pocket and let the bomb roll from her grasp. It landed right at her feet, one step from the two of Them on the sled. Lorence heaved his own burning grenade toward the two with shock rods. The precision of his throw amazed Josef, but Lorence had thrown a lot of these bombs, and knew how far they would roll.

Joni’s grenade detonated first, and she vanished in a cloud of smoke, debris and a blue-green mist of alien blood. Lorence’s bomb went off between the two holding shock rods, cutting them both down like wheat before the scythe. Several people nearest to the blast also fell.

Josef was moving forward before the smoke thinned, stepping over fallen neighbors whose screams he could just hear over the ringing in his ears. Others moved with him, some kneeling to tend the injured, but Josef had a different job. Past the last of his fallen neighbors lay the two aliens, one torn wide open by the force of the blast, the other flopping randomly, three toed feet flailing on the ends of stubby shredded legs.

Josef snatched up its fallen shock rod and brought the butt end down as hard as he could on the wounded thing’s head. A squeal like a slaughtered pig’s split the air, teal-hued meat and shattered bone clinging to the end of the shock rod as he brought the heavy instrument down once again to silence the din.

“Lorence!” he bellowed, scanning the crumpled forms for the one who was their only hope. “Lorence, where are you?”

“Josef!”

He looked toward Mira’s shrill call and found her kneeling next to a boy with his knee torn open by shrapnel. He cringed, but there had been no alternative, and those in the front-most ranks had agreed to the plan. They had all agreed. He squinted past the smoke and blood to see his wife pointing frantically toward the hover sled.

“He’s there!” she screamed before turning back to the boy’s ravaged leg.

Josef lunged toward the hover sled, knowing what he would find and praying to all the gods he didn’t believe existed that a shred of sanity remained in his friend’s mind. He found Lorence clutching Joni’s crumpled form, misery escaping his throat in gasps of incoherent sound.

Pity grasped Josef’s heart in a vice, but if they had one chance, one flashing hope of becoming more than an example to all the rest of the human communities dotting Earth’s endless rural landscape, it lay in this man. He grasped Lorence’s shoulders and lifted him up. Joni sagged in the smaller man’s grasp, a torn rag doll staring into nothing with a mien of utter peace on her gentle features. He eased the woman’s body down with one arm, gripping Lorence’s wrist firmly with the other.

“You got to let her go, Lorence. We need you!” He pulled the man away from his dead wife and forced him to meet his eyes. “You with me, Lorence? You here?”

“She… she…” Madness flowed from the smaller man’s eyes, hardening into a dark core of hate.

Good, Josef thought, hating himself for it. Hate is something I can use.

“She’s dead, Lorence! She died to help us! Don’t let her die for nothin’!”

“She…. No! No, I won’t!” The man’s stance firmed under Josef’s broad hands, and he eased his grip. Hate won out over madness, then eased into resolve and conscious thought. “Clear the sled, Josef. Call the volunteers up and send the rest away. I don’t have long to figure this thing out, and I don’t need any help.”

“Right.” Josef did as he was told, calling to those milling about without purpose to help.

They cleared the deck of the sled, and everyone who had volunteered to help armed themselves doubly and triply with the grenades of those who would stay behind. Among the throng he found Mira helping to bind a broken arm.

“Take them all to the hills, Mira. They’ll blow this place to hell as an example when we’re—when we’ve done what we can.”

“Josef, I’m sorry,” she said, anguish ripping at her throat. “None of this would have happened if I—”

“If you hadn’t, none of us would ever have a chance to be free, Mira.” He grasped her and looked into her eyes for the last time. “You can light the fire in them, Mira, just like you did in me. You got Lorence’s recipes. You can make more bombs and give them to others. Take our people to the caves and show the rest how we did this. Send them out to others. Spread the word! Spread the knowledge that we can kill these things!”

“I will,” she said, and in the depths of her obsidian eyes, he saw that she would.

***

“How are you doing this?” Josef yelled over the wind, swaying a little as the sled yawed with a strong gust.

“It’s easier than it looks. The machine does most of it, I just tell it where to go.”

Josef was glad it was easy, because the vast drop a foot from his knee worried him more than the looming shape of the flying alien city darkening the sky ahead of them. The two men crouched behind the broad control panel of the sled as others held up the slumping corpses of the aliens they’d killed. He watched Lorence fiddling with two small sticks and several lighted nobs that controlled the craft. The long minutes of experimentation Lorence had taken to learn the controls had left Josef doubtful, especially after he’d dumped the craft on its side, twice.

Now, as they neared the immense city-ship that hung like a floating mountain above the plain, Lorence’s mastery of the craft seemed complete. They flew straight for the gaping slit in the behemoth’s belly, the last in a stream of hundreds of other hover sleds returning to the mother ship with their harvest. Josef looked back at the grim men and women who had volunteered to come along, and a stoic calm settled over him. They would do what they could, die if they must, kill if they had the chance, but victory wasn’t part of the plan. This wasn’t a fight they could win, but it was a fight they could start.

He clutched the shock rod and the four heavy spheres tucked into his shirt, vowing to be first off the sled when they reached their final destination.

***

Mira stood at the mouth of the cave watching the smoldering ruin of the new mountain that had recently fallen from the sky. The impact had shaken the very Earth, but it had also given hope to the hundreds of people who had packed up their entire lives and fled into the hills. The fall of the alien city-ship had told every human in a two-hundred-mile radius that resistance was possible, that They could be fought, could be killed.

Her husband was gone, but she would bear more children for him, one every year, and each one would learn the legend of their father, Josef, and how he had brought the mountain down. They would grow up in the wilds, afraid, hungry and always on the run, but they would grow learning how to fight, how to plan and how to take their planet back from those would treat humans like livestock.

The harvest was over.

The war had begun.